I would like to propose a new disorder for the American Psychiatric Association to consider in its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: that of confusing a diagnosis with being a real thing unto itself. A recent New York Times article from April 1, 2013, reported that one in every five high school boys and 11% of all children are diagnosed as having attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

My contention is that nobody has ADHD, because it doesn’t exist. The acronym ADHD simply describes behaviors and conditions that may correspond with a diagnosis, which we created. As with all diagnoses, when we confuse the description with being an actual entity, we trick ourselves and exacerbate the problem.

A psychiatric diagnosis should be descriptive rather than a statement of an objective reality. It should therefore delineate tendencies of behavior and personality as well as emotional and psychological patterns that a clinician observes, which should thereby facilitate our understanding and treatment. The concept of reification refers to taking an abstract idea and turning it into a real thing. This is precisely what occurs with diagnoses. They take on a life of their own. Referred to as the “fallacy of misplaced concreteness” by the philosopher Alfred North Whitehead, mind creates something – in this case, ADHD – and then denies its own participation in having done so.

If I hear a colleague say, “Jane has ADHD,” I may respond, “I have no idea what you’re saying. How can Jane have a disorder that didn’t exist until we in fact coined the term to describe it?” It would, however be accurate to say, “Jane exhibits behavior consistent with what we call ADHD.”

What’s the difference, you might wonder? In the former example Jane appears to have an affliction, yet it’s not objectively discernible as in the case of cancer, high blood pressure, or the West Nile virus. The diagnosis is a matter of subjective interpretation and needs to be acknowledged as such. If it’s not, we may fall prey to seeing this disorder wherever we look for it and, thus, may become influenced and further biased in our diagnosis.

What You Look for Is What You’ll See

I acknowledge that untold numbers of people suffer problematic or challenging obstacles that may align with the diagnosis of ADHD. We should first and foremost be asking why this is occurring. Are these diagnoses rising so precipitously because clinicians are being trained to look for these symptoms? What we look for is what we see, after all. In part, this growing incidence of confirmation bias may account for the rise in cases, but it is certainly furthered by the influence of the pharmaceutical industry and its profit motivation.

Moreover, if we examine our cultural condition, one could make a very convincing argument that our entire society exhibits and promotes behavior consistent with what we call ADHD. Certainly, the addictive relationship that we have with our electronic technology prompts such behaviors. Even executives sitting in boardrooms and members of Congress at the State of the Union address distract themselves by texting or browsing the web. These people are at the pinnacle of achievement in our country. Why aren’t we medicating them, which also begs the question why do we expect more obedient behavior from our children?

Many physicians and therapists act negligently, or worse, by casually prescribing amphetamines to children without an exhaustive and comprehensive evaluation. Do they take the time to inquire as to the family environment and interpersonal relationships, the child’s diet and exercise habits, or teacher’s demands for conformity? And how often are children medicated because of an overbearing pressure from parents who won’t tolerate anything less than complete focus and stellar academic performance?

Before we alter the brains of our children with amphetamines, we owe them some serious due diligence. Although there are many individuals that may have benefitted from such medication, a one-size-fits-all approach that blankets our children with serious psychotropic medication speaks mightily of where our society has come.

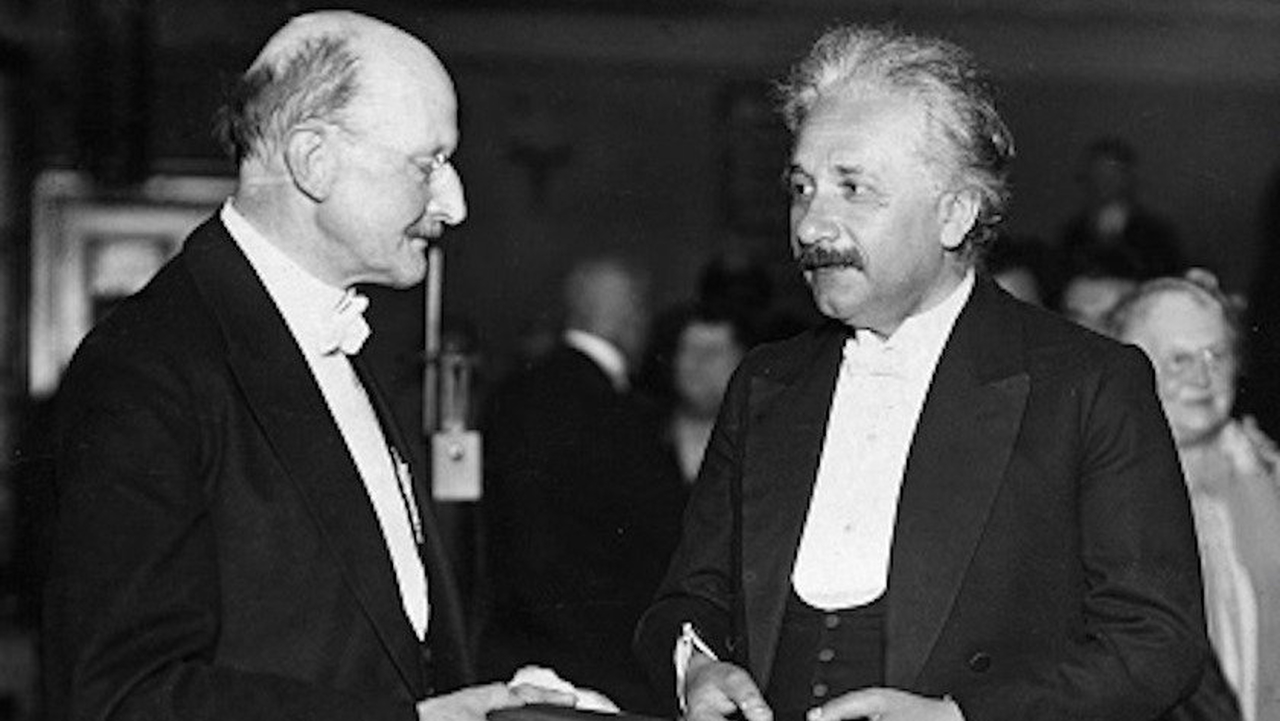

On another note, perhaps our runaway emphasis on performance, with its accompanying requirement for focus and attention, has taken us far from a balanced lifestyle and mindset. We have obscured and diminished our value for wonder and curiosity in our lives – and we undoubtedly suffer for that. It’s a good thing Albert Einstein isn’t a teenager in America today. Einstein was not known so much for his focus and diligence as he was for his sense of wonder. Just recall his assertion: “Imagination is more important than knowledge.”

More from Mel

Podcast #109 Over-Simplifying Equals Dumbing Down

I don’t quite agree with the “non-existence” part of ADHD, Mel, but – must admit – I did have to smile at the “Diagnosis Disorder” idea.

On the other hand, I think it makes sense to explore approaches like neurofeedback more; particularly at early ages. We think nothing of taking strong medications [of which I am NOT against taking, but rather feel a lot more cautious, than flippant, like I used to feel].

I thought I remember reading that there was finally to be a large-scale study conducted using neurofeedback [or was that just a nice dream?!].

There is a good meta-analysis on the use of Neurofeedback for ADHD in the Journal ‘clinical EEG and neuroscience’ vol 40 no. 3 July 2009

Efficacy of Neurofeedback treatment in ADHD: The

effects on Inattention, Impulsivity and Hyperactivity:

A meta-analysis.

Martijn Arns Sabine de Ridder Ute Strehl Marinus Breteler Ton Coenen

abstract:

Since the first reports of Neurofeedback treatment in ADHD in 1976 many studies have been

carried out investigating the effects of Neurofeedback on different symptoms of ADHD such

as inattention, impulsivity and hyperactivity. This technique is also used by many

practitioners, but the question as to the evidence-based level of this treatment is still unclear.

In this study selected research on Neurofeedback treatment for ADHD was collected and a

meta-analysis was performed.

Both prospective controlled studies and studies employing a pre- and post-design found large

effect sizes (ES) for Neurofeedback on impulsivity and inattention and a medium ES for

hyperactivity. Randomized studies demonstrated a lower ES for hyperactivity suggesting that

hyperactivity is probably most sensitive to non-specific treatment factors.

Due to the inclusion of some very recent and sound methodological studies in this metaanalysis

potential confounding factors such as small studies, lack of randomization in

previous studies and a lack of adequate control groups have been addressed and the clinical

effects of Neurofeedback in the treatment of ADHD can be regarded as clinically meaningful.

Four randomized controlled trials have shown Neurofeedback to be superior to a (semiactive)

control group, whereby the requirements for Level 4: Efficacious are fulfilled (Criteria

for evaluating the level of evidence for efficacy established by the AAPB and ISNR). Three

studies have employed a semi-active control group which can be regarded as a credible

sham control providing an equal level of cognitive training and client-therapist interaction.

Therefore, in line with the AAPB and ISNR guidelines for rating clinical efficacy, we conclude

that Neurofeedback treatment for ADHD can be considered ‘Efficacious and Specific’ (Level

5) with a large ES for inattention and impulsivity and a medium ES for hyperactivity.

Mel – this is an extremely well-written, and thought-through, piece. Thank you for bringing it to the fore. I fully agree with you, and support your position of such diagnoses as being truly made up, and dangerously so. If there’s any criticism I have for what you’ve written, it is that you did not go far enough in vilifying the pharmaceutical companies for their part in perpetuating ADD/ADHD as a “disease”…so to increase prescriptions/sales of their psychotropic drugs, as well as their obscene profits.

I believe that the perpetuation of this “disease conceptualization” has yet another psychological impact — it erodes an individual’s internal locus-of-control orientation (i.e. sense of self-efficacy), but removing from his/her mindset the concept that we as individuals have the capacity to choose different thoughts, and thus, different behaviors. Yes, there is a challenge in terms of clearly understanding those choices, and the dynamics thereof, but that’s certainly where bio/neurofeedback can come into play.

Those who are brainwashed into thinking that they (or their child) has a disease (i.e. “there’s this thing inside of me and there’s nothing I can do about it”) are naturally more inclined to accept the easy way out of the problem — pop a pill. This conveniently removes from them the obligation to extend any real effort toward addressing the “root cause” of the problem themselves. And such a cognitive response (or lack thereof) is an addiction in and of itself.

Add to this the neuro-scientific tendency for the brain to prioritize routine activities (e.g. popping a pill each morning), rather than taxing the energy-hoarding brain’s executive functions, which would be called upon in the sort of strategic treatment responses that you are suggesting. Yes, our brains are “lazy,” perhaps out of necessity, but the dynamic you’re highlighting here exploits that…mercilessly.

well said Charlie…more to come

Thanks for this. I liked the premise of Diagnosis Disorder. I know a young adult who has multiply challenges due to fetal alcohol and/other intrautero exposure. She had and still retains an exceptional ability to focus (since the age of 3) when she is engaged with the visual arts, drawing, painting, mastering Japanese pictograms, and has tested in the top 90% group for visual perception and visual memory.

Academic work, English, math, history and science remain extremely difficult in terms of steady focus and memory. She has never been medicated for ADHD. College is a huge struggle to get assignments, complete and turn them in on time.

What is your suggestion for her? How can she transfer or learn to use her natural visual memory for academic subjects?

Hi Mel, refreshing read I must say. I’ve began a new blog and part of it is my interviewing ‘interesting people’ for want of a better term! I recently sat down with someone to discuss what it’s like to hold down a job, while being held down with depression. Interesting read; thought it might interest you:

Keep up the great work!

I was diagnosed with “ADHD” and heavily meditated in the 3rd grade. I think that being on that medication eventually led to the substance abuse problems I faced in High School. I have since cleaned my act up, and am currently functioning as a responsible adult with no ADHD medication! Great post!